Europe Post-War, Art and Politics

Gertje Utley

Europe Post-War, Art and Politics

Gertje Utley

section 4

And in the 1960s it even became acceptable to depict people at play and allude to the beginnings of a modest version of the consumer society. [65]

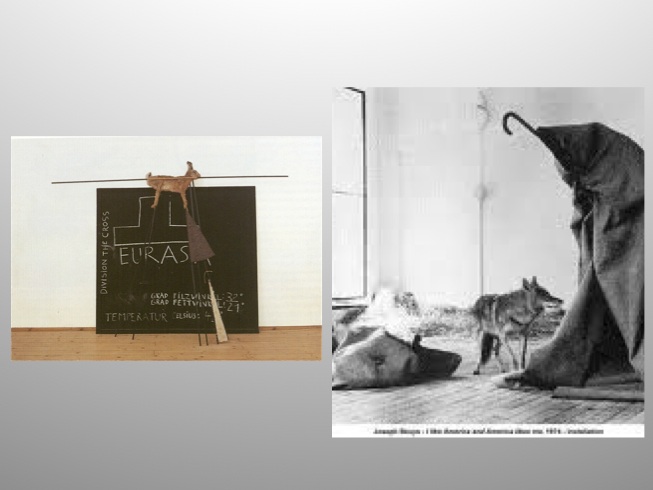

Joseph Beuys, Eurasia, 1963; Joseph Beuys, I love America, and America loves me, 1974

In West Germany, as elsewhere in the western art world, art practices expanded beyond traditional categories in the 1960s and 70s to include performance art, video, ephemeral and multiple works of art. [66]

Much of this was politically motivated against the new consumer society and as a critique of the older generation, whose authority was now being questioned in light of new revelations of Germany’s Nazi past. The most important and influential artist of his generation was Joseph Beuys. A political activist, Beuys believed in art’s potential to transform society. Through the inclusion of performances, environments, documents, multiples, and drawings, Beuys aimed at the fusion of art and life. He tailored his art and personality on the model of the shaman, the artist healer of primitive hunting societies who served as mediator between society and its ills and the forces beyond.

In his performance “Ausfegen,” literally sweeping clean, he and two students used a red broom to clean up the debris left over from a left-wing May-Day demonstration on the Karl Marx Platz in East Berlin, demonstrating thereby that his critique is directed as much at the Soviet controlled east as the capitalist West. [67]

Beuys was also the first German artist to try to deal with the commemoration of the Holocaust. His sculpture “Auschwitz Demonstration” belongs to what he called his “social sculptures”. In a vitrine, resembling a medical cabinet, he positioned two blocs of fat on top of a cooker, which is not plugged in and is therefore unable to provide the necessary heat to warm the fat and depriving it of its malleability.

For Beuys fat, as well as bees’ wax were in their malleability symbolic of the transformative qualities he aimed for in his art. [68] In his procedure, his use of happenings, Beuys was heavily influenced by Fluxus. Fluxus, an international movement that had originated in the U.S., was based on the concept of Dada inspired anti-art, which aimed at recreating the experience of being part of the real world. [69] Beuys’ famous claim that everyone is an artist has to be understood under that angle. His most famous Fluxus event in 1963 started with a happening, in which Beuys filled a discarded piano with candy, dried leaves, and laundry detergent. What he wanted was to create was (I quote) a “healthy chaos” as protest against the official hypocrisy in the face of continued violence and torture in the world. [70] What resulted from the “healthy chaos” was Beuys bloodied nose and its famous press photo, which came to be viewed as iconic for the power of art as player in the cycle of violence and redemption.

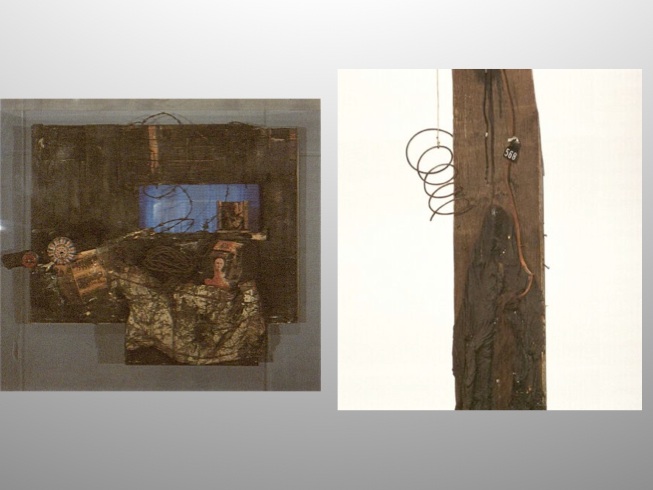

Wolf Vostell was also among the earliest artists to commemorate the holocaust. In his work the use of discarded and found objects addresses the violence he sees as inherent in technology. His assemblage Black room is a combination of such objects set on a pedestal in a dark gallery, and lit only by the television screen in the assemblage and the Auschwitz floodlight that we see on the left screen. [71]

1960s initiated Germany’s serious confrontation with it’s Nazi past, which was finally triggered by the trials in Jerusalem and Frankfurt in 1961 and 1963-65 against Nazi crimes related to the Holocaust. The resulting revelations and those about the presence of old Nazis as part of the German government contributed considerably to the politization of the West German Youth. [72]

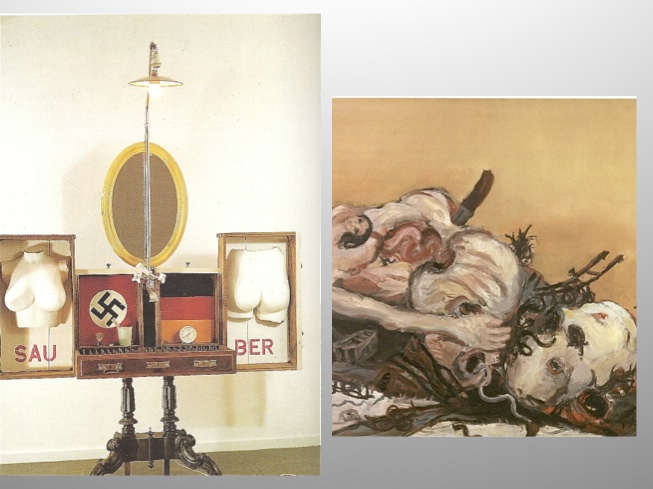

Georg Baselitz, Bild für die Väter, 1965

The public discussion of the crimes of the past created a harsh climate of generational strife in which the generation of the parents was aggressively questioned about their role in the Nazi crimes..Hans Peter Alvermann’s construction barely needs an explanation, so obvious is the imagery. Sexual imagery has long been used in German art in particular to denounce the perversions of society. Its juxtaposition with the German flag and the Swastika makes its political content even more pronounced.

Among the most prominent artists to address this difficult subject, starting in the late 60s, were Georg Baselitz, Markus Luepertz, Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer, all adopting a new realist and figurative idiom. Apart from Kiefer, most of those artists had come from East Germany, where they were trained under the imposition of Socialist Realism.

The title of Georg Baselitz’s “Bild für die Vaeter” (painting for the fathers) 1965, clearly denounces those he views as responsible for the war. The decomposing bodily mass speaks of physical as well as moral violence in its use of figuration in an almost abstract aggressive application of paint. While his work shows the effect of the paintings by de Kooning, Pollock, Rothko and Guston that Baselitz had seen at an exhibition of New American painting in 1958, it purposefully straddles the demarcation between abstraction and figuration. [73]

Baselitz was born Georg Kern just before WWII in what would become East Germany. In 1957 he fled to West Berlin, where he changed his name to Baselitz, based on Deutschbaselitz his hometown in East Germany. In the West he discovered the works of the German Expressionists, which he reflects stylistically but not in spirit. Instead of the Brücke artists’ utopian Weltanschauung, Baselitz focused instead on expressions of alienation. [74]

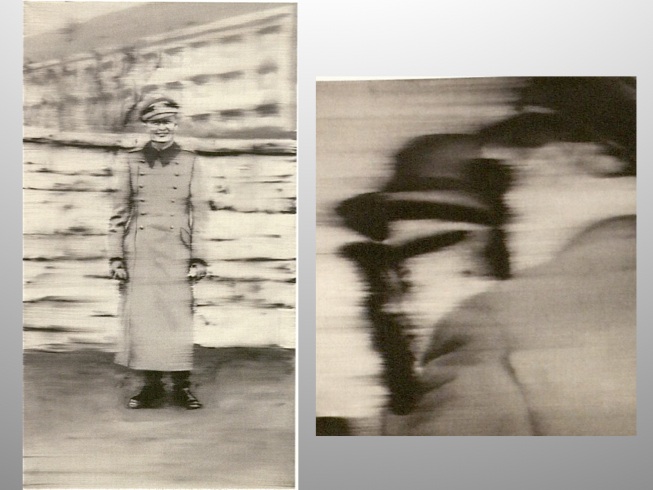

With their paintings “Eagle” both Baselitz (on the left) and Gerhard Richter (right) took a motif that was tied to feelings of German nationalism since the 19th century. Baselitz, by painting the motif upside down, a habit he had adopted in 1969, neutralizes its symbolic content, similar to the technique of alienation that Brecht employed in the theater. [75] Richter achieved a similar distancing through the blurred effect of his paintings.

Much of Richter’s work was copied from old photographs, frequently of his family. He literally throws a fog over those memory images, addressing his resistance to memorizing the past. This picture of his uncle Rudi who died in the war in 1944, raises the heavy questions that were very much on young Germans’ minds at the time: to what degree did my parents collaborate in the Nazi crimes?

Like Baselitz, Richter too was born in East Germany and had trained there as a Socialist Realist mural painter at the Dresden Academy of Art. In 1961 just before the erection of the wall, he fled to the West. [76]

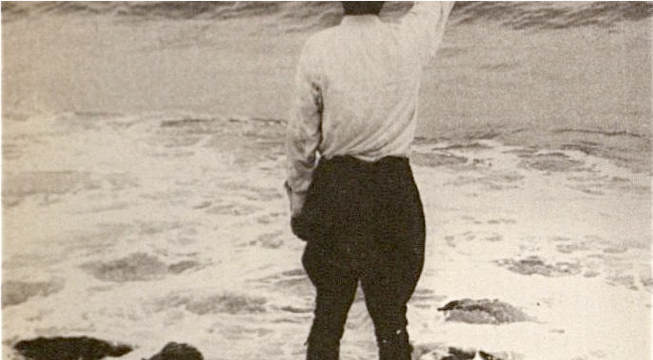

Iconic images of the German Nazi past appear also – and most insistently – in the art of Anselm Kiefer, a student of Joseph Beuys’. In “Besetzungen” in the late 1960s Kiefer had himself photographed executing the Hitler salute in various European locations that during the war had been under German occupation. Not always recognized as a satire of the Nazi past, his imagery was frequently accused of being proto-fascist. [77] He claimed however, that his reenactments of Nazi imagery was his way of coming to terms with the burden of the past. [78]

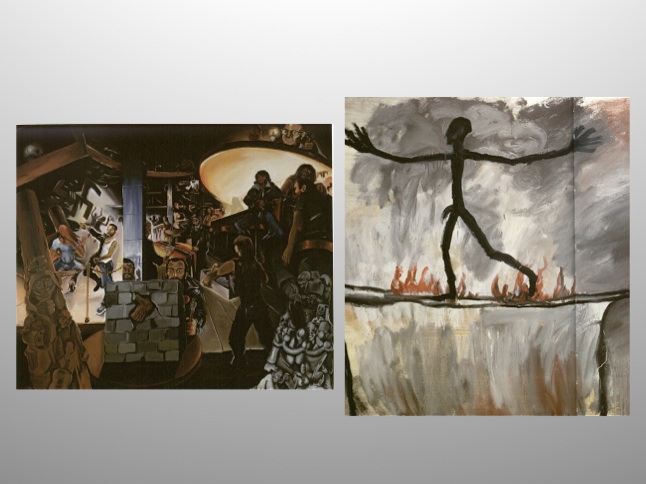

Many of Kiefer’s paintings focus on sites of German history and identity, such as this painting called Varus, the name of a Roman general, who was defeated by Germanic tribes in a historic battle in 9 AD. Many of his works recall the monumentality of Speer’s architecture or indeed one of the grandiose sets for one of the many Nazi ceremonies, as in this painting, Germany’s Spiritual heroes, in which he names Joseph Beuys along with Richard Wagner, whose belief in the redemptive power of art he shared. [79]

Essentially what this new realism, so different from the Socialist realism in the East, strove for was to explore the past and why it had taken so long to be acknowledged. [80]

While the past was an eminent subject for artists in the 60s and 70s, the present and notably the division of Germany appeared much more rarely in the arts.

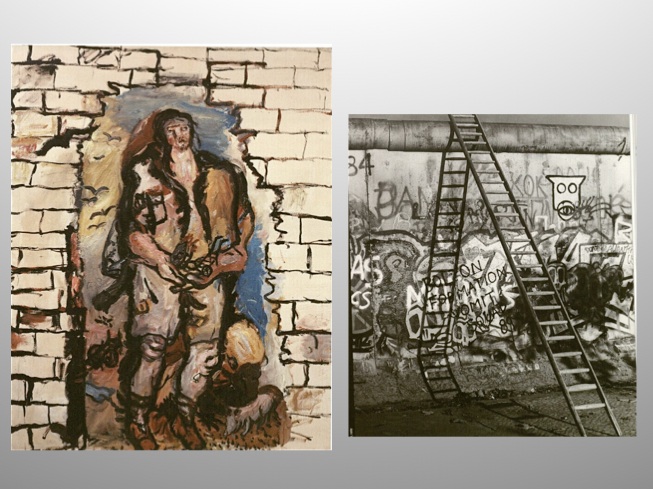

One of the exceptions is Baselitz’ “Der Hirte,” (the shepherd) of 1965, in which the artist represents himself literally breaking through a wall. We must remember that this was 4 years after the construction of the wall that would physically separate the West from the eastern part of Germany and made the artist’s return to his hometown totally impossible. [81]

Two other artists addressed this topic; one from the West and one from East Germany: Joerg Immendorf and A.R. Penck.

Immendorf, perturbed by the lack of dialogue between the two artist communities, actually travelled to East Berlin to meet A.R. Penck, with whom he founded what they called an exchange and action alliance.

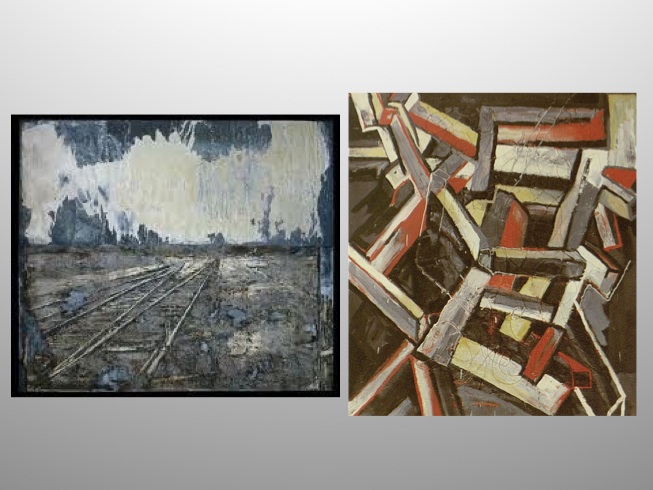

His painting “Café Deutschland” of 1977 is set in a disco and carries references to a variety of issues. Like the art of Richter, Kiefer, Baselitz and others he includes symbols of national identity: the German flag, the Imperial eagle as well as the swastika. But he also includes elements of the historical present with the presence of two border towers between the two Germanys. Berthold Brecht can be recognized over the bar, and the artist himself is reaching his hand through a hole in the wall. It was Jorg Immendorf who developed the image of the leftist German artist. Yet he belonged to a sect of Maoists who considered the Soviet Union worse than the capitalist West, and in the mid 70s left the movement. [82]

A.R. Penck, in “Der Uebergang”, The Passage or the Crossing of 1963 also refers to the brutal and divisive reality of the Berlin wall.

Maybe the most moving artworks to memorize the war and the holocaust is this work, Missing House of 1990 by the French artist Christian Boltansky. The missing house, which stood in Berlin’s Jewish quarter near the New Synagogue, was destroyed on the night of February 3, 1945. Simple white signs on the opposing house walls display the names of its former inhabitants. The mostly foreign names and the dates 1943, 44, 45 add to the implied violence of the work.

This photo of the fall of the Berlin wall, really illustrates the end of the postwar period. With the fall of the Soviet Union, issues such as the battle between Socialist Realism and abstraction were no longer relevant.

In conclusion, we saw that British post-war art really lacked any significant political component before the 1970s, other than an overall reaction of anxiety born from the experience of war and the fear of nuclear annihilation. The French, and to a lesser degree the Italian art scenes were dominated by the realism versus abstraction debate along the left right political divide, while East Germany did not allow any political or even artistic debate under the strict imposition of Socialist Realism. It was really in West Germany that you had the most interesting political art, which grew out of its specific postwar situation and a memory process, which is still ongoing while most of the other debates have lost their relevance.

References:

On the political background of the era:

Thomas Crow, The rise of the sixties: American and European art in the era of dissent. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Nancy Jachek, Politics and painting at the Venice Biennale, 1948-64. Manchester, New York: Manchester University Press, 2007.

Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. New York: The Penguin Press, 2005.

On British art during the period:

David E. Brauer, Pop art: U.S. / U.K. connections, 1956-1966. Houston, Tx: Menil Collection in association with Hatje Cantz, 2001.

Mona Hadler, “Sculpture in Postwar Europe and America, 1945-59,” Art Journal 53, no. 4 (Winter 1994): 17.

James Hyman, The Battle for Realism, Figurative Art in Britain during the Cold War, 1945-1960. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2001.

“Staying Socialist: Attacks on Social realism,“ in James Hyman, The Battle for Realism, Figurative Art in Britain during the Cold War, 1945-1960 (2001), p. 173-189.

David Mellor, “Existentialism and Post-War British Art,” Paris Post-War, p. 53-61.

David Alan Mellor and Laurent Gervereau, The Sixties in Britain and France, 1962-1973; the utopian years. London: Philip Wilson, 1997.

Menil Collection, Houston Pop Art. U.S./UK

Henry Meyric Hughes and Gijs van Tuy, Blast to Freeze: British art in the 20th Century Wolfsburg: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg. New York: Hatje Cantz, 2002.

On French art in the postwar era:

Aftermath: France 1945‑1954; new images of man. London: Barbican Center for Arts and Conferences, 1982.

Dominique Berthet. Le P.C.F., la culture et l'art. Paris: La Table Ronde, 1990.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, Après la guerre. Paris: Gallimard, 2010.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac. L'Histoire de l'Art; Paris 1940‑1944. Ordre national, traditions et modernité. Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne, 1986.

Philippe Buton. La France et les Français de la Libération: 1944‑1945. Paris: Bibliothèque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine and Musée d'Histoire Contemporaine, 1984.

David Alan Mellor and Laurent Gervereau, eds., The Sixties in Britain and France, 1962-1973, the utopian years. London: Philip Wilson, 1997.

Frances Morris, ed., Paris Post-War: art and existentialism, 1945-1955. London: Tate Gallery, 1993.

Gertje Utley, "Picasso and the French Post-war 'Renaissance': A Questioning of National Identity," in Jonathan Brown, ed., Picasso and the Spanish Tradition. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996, 95-118.

———. Picasso: the Communist Years. London & New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

———. "From Guernica to The Charnel House: The Political Radicalization of the Artist," in Steven A. Nash and Robert Rosenblum, eds., Picasso and the War Years 1937-1945. New York: Thames and Hudson, Inc., 1998.

German art during the postwar era:

Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann, eds., Art of two Germanys: Cold War Cultures. New York, London, Los Angeles: Abrams in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2009.

Stephanie Barron, “Blurred boundaries: the art of two Germanys between myth and history,” in Barron and Eckmann, eds., 2009.

Chicago, Ill., Negotiating history: German art and the past. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2002.

Eckhart Gillen, German art from Beckmann to Richter: images of a divided country. Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, distributed by Yale University Press, 1997.

Dieter Honisch, Kunst in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1945-1985. Berlin: Nationalgalerie, 1985.

Andreas Huyssen, “Trauma, violence, and memory: Figures of memory in the course of time,” in Barron and Eckmann, eds., 2009; 225-239.

Barbara McCloskey, “The internationalization of german art. Dialectic at a standstill: East German Socialist Realism in the Stalin era,” in Barron and Eckmann, eds., 2009.

Peter Weibel: “Repression and Representation: The RAF in German Postwar Art” in Barron and Eckmann, eds., 2009; 257.

NOTES

[1] Tony Judt, Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. New York: The Penguin Press, 2005, pp. 16-23.

[2] Judt, pp. 52-58.

[3] Tony Judt. Past Imperfect: French Intellectuals, 1944‑1956. 2nd ed. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: 1994, 223. On the history of the Cold War see also John lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: a new history. André Fontaine. Histoire de la guerre froide (2 vols.). Paris: Fayard, 1965 and 1967. Annie Kriegel. Ce que j'ai cru comprendre. Paris: Robert Laffont, 1991, p. 368.

[4] Nancy Jachec. Politics and painting at the Venice Biennale, 1948-1964: Italy and the idea of Europe. Manchester, New York: Manchester University Press, 2007, p. ?

[5] James Hyman, The Battle for Realism, Figurative Art in Britain during the Cold War, 1945-1960. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2001; p. 4

[6] Martin Harrison, Transition: the London art scene in the 1950s. London: Merrell, 2002; p. 4; Simon Wilson. British Art: from Holbein to the present day. London: The Tate Gallery Publications, 1979, p. 153.

[7] Henry Meyric Hughes and Gijs van Tuy. Blast to Freeze: British art in the 20th Century. Wolfsburg: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg. New York: Hatje Cantz, 2002, p. 175.

[8] Hyman, p, 41; Wilson, p. 153.

[9] Henry Meyric Hughes and Gijs van Tuy. Blast to Freeze: British art in the 20th Century. Wolfsburg: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg. New York: Hatje Cantz, 2002, p. 107.

[10] Hyman, p. 4; Meyric Hughes and van Tuy, p. 117.

[11] Meyric Hughes and van Tuy, p. 107.

[12] Cited in Mona Hadler, “Sculpture in Postwar Europe and America, 1945-59,” Art Journal 53, no. 4 (Winter 1994): 17; David Mellor, “Existentialism and Post-War British Art,” in Frances Morris, Paris Post-War: art and existentialism, 1945-1955. London: Tate Gallery, 1993, pp. 53-61.

[13] Harrison, p. 50.

[14] Mellor, pp. 53-61.

[15] Hadler, p. 17; Mellor, p. 53.

[16] Herbert Read’s words are part of his critic of the Venice Biennale of 1952 and are quoted in Mellor, p. 55; Harrison, p. 6, 68.

[17] Mellor, p. 55; Harrison, p. 74.

[18] Joan Marter, “The Ascendency of Abstraction for Public Art: The Monument to the Unknown Political Prisoner Competition,” Art Journal 53, no. 4 (Winter 1994), pp. 28-36.

[19] Hyman, pp. 4, 7,8.

[20] Hyman, pp. 16, 25; and “Staying Socialist: Attacks on Social realism, “ in Hyman, pp. 173-189.

[21] Hyman, p. 6; Harrison, p. 74.

[22] Hyman, pp. 179-181.

[23] Wilson, p. 177.

[24] Meyric Hughes and van Tuy, pp. 139.

[25] Meyric Hughes and van Tuy, pp. 139.

[26] David Brauer, ed., Pop Art: U.S./UK. Connections, 1956-1966. Houston, TX: Menil Collection, 2001, pp. 24, 25.

[27] Harrison, p. 92.

[28] Harrison, p. 92.

[29] Meyric Hughes and van Tuy, pp. 143, 175.

[30] Jachec, pp. 18, 24.

[31] Jachec, p. 31

[32] Hyman, p. 77.

[33] Frances Morris, Paris Post-War: art and existentialism, 1945-1955. London: Tate Gallery, 1993, p. 89. On this period see also Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, Après la guerre: Art et artistes. Paris: Gallimard, 2010.

[34] Morris, p. 129.

[35] Verdès-Leroux. Au service du Parti: le parti communiste, les intellectuels et la culture (1944‑1956). Paris: Fayard/Éditions de Minuit, 1983, p. 271.

[36] Roger Garaudy, "Artistes sans Uniforme," Arts de France, no.9 (1946): 17. Louis Aragon, "L'Art 'zone libre'?" Les Lettres françaises (29 November 1946), pp. 1, 4 : "...je considère que le parti communiste a une esthétique, et que celle-ci s'appelle le réalisme...". See also René Guilly, "Faut-il une esthétique au Parti Communiste?" Juin, 10 December 1946.

[37] On Aragon's role in the promotion and later in the end of Socialist Realism see Pierre Daix. Aragon, une vie à changer. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1975, part II, in particular chapter 1 and 3. See also Aragon's epigraph upon Zhdanov's death "Zhdanov et nous," Les Lettres françaises, 9 September 1948, pp. 1, 5.

[38] Ibid.

[39] The FCP was largely financed by Moscow. According to Annie Kriegel each member of the French party's leadership operated under a Soviet superior, so that every Soviet conflict was reflected in the French Communist party.

[40]Claude Roy provoked Thorez with his protest against the harsh criticism in l'Humanité of a writer who had not shown enough enthusiasm for the work of one of the Socialist Realist party painters. Picasso who was present remained silent. Claude Roy, Somme toute. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1976, pp. 89. See also Laurent Casanova "Responsabilités de l'Intellectuel Communiste." Cahiers du Communisme 26, no. 4 (April 1949), pp. 443‑459.

[41] Louis Aragon, "Réalisme socialiste et réalisme français," La Nouvelle Critique, 6 May 1949, pp. 27-39. The article also contained Aragon's poem "My party has returned to me the national colors of France." See for ex. Jean Milhau. "Le Nouveau Ralisme." Arts de France 21‑33 (1948), pp. 33‑46. Taslitzky 1949, 77-83; and Taslitzky, "Jalons sur fond brulant," 5; also Sarah Wilson, Art and the Politics of the Left in France, ca. 1935‑1955. London: Ph.D. diss. Courtauld Institute, 1993, p. 315.

[42] Aragon 1952, 72.

[43] Jean Bouret, "Comment concilier Picasso et Fougeron, tel est le problème," Franc Tireur, cited in Wilson 1993, p. 370.

[44] Cited in Daix 1976, 283 "It is at his battlements of Peace Partisan that Picasso painted the dove and it is at his battlements of Communist militant that Fougeron painted Le Pays des Mines."

[45] Taslitzky’s painting, The Death of Danielle Casanova, was an homage to the wife of Laurent Casanova. She had died in a concentration camp and became one of the most sanctified martyrs of Communist lore, frequently compared to Jeanne d'Arc.

[46] See Aragon 1947, and his "Pour un réalisme véritable," Les Lettres françaises, no. 490 (12 November 1953), cited in Ristat 1981, 67-72, 131-134.

[47] J.R., "Idées et problèmes d'aujourd'hui," Arts de France, no.34 (January 1951): 75.

[48] Jean Ristat. ed. Aragon: écrits sur l'art moderne. Paris: Flammarion, 1981, p. 72; "André Fougeron, dans chacun de vos dessins se joue aussi le destin de l'art figuratif, et riez si je vous dis que se joue aussi le destin du monde".

[49] On the contemporary debate see for example: Les Amis de l'Art, “Pour et contre l'art abstrait”. Paris: Cahiers des Amis de l'art, no.11, 1947; Estienne 1950; Auguste Herbin, L'art non-figuratif, non-subjectif, Paris, 1949; Jean Bouret, "Projet de manifeste pour un art humain," Arts, 20 December 1946; Léopold Durand, "La grande querelle de l'art abstrait," Les Lettres françaises, 1 August 1947; Léon Degand, "Défense de l'art abstrait," Les Lettres françaises, 2 August 1947; Hermarque, "Humanisme et Art abstrait," Arts, 8 November 1946; Jean Loisy, "Propos sur l'Art abstrait," Arts, 2 August 1946.

[50] Françoise Gilot and Carlton Lake. Life with Picasso. New York: McGraw‑Hill, 1964, p. 72; Hélène Parmelin. Picasso says, translated by Christine Trollope. South Brunswick, N. J.: A.S. Barnes, 1969, p. 104.

[51] Stephanie Barron, “Blurred boundaries: the art of two Germanys between myth and history,” in Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann, eds., Art of two Germanys: Cold War Cultures. New York, London, Los Angeles: Abrams in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2009, p. 12.

[52] Andreas Huyssen, “Trauma, violence, and memory: Figures of memory in the course of time,” in Barron and Eckmann, eds., 2009, p. 228.

[53] Peter Weibel: “Repression and Representation: The RAF in German Postwar Art” in Barron and Eckmann, eds., 2009, p. 257.

[54] Huyssen, in Barron and Eckmann, eds., 2009, p. 226.

[55] Cornelia Homburg, “German Art: Why Now?” in Cornelia Homburg, ed. German Art Now. St. Louis, London, New York: St. Louis Art Museum and Merrell, 203, pp. 13, 14.

[56] Barron in Barron and Eckmann, p. 15.

[57] Barron, in Barron and Eckmann, pp. 15, 136.

[58] Barron in Barron and Eckmann, p. 39; Huyssen in Barron and Eckmann, p. 229

[59] Huyssen in Barron and Eckmann, p. 229.

[60] Barbara McCloskey, “Dialectic at a Standstill: East German Socialist Realism in the Stalin Era,” in Barron and Eckmann, p. 105.

[61] Barron in Barron and Eckmann, p. 16, 17; McCloskey in Barron and Eckmann, p. 105.

[62] Ursula Peters and Roland Prügel, “The Legacy of Critical Realism in East and West,” in Barron and Eckmann, p. 68.

[63] McCloskey in Barron and Eckmann, p. 113.

[64] Idem, p. 110.

[65] Idem, p. 110.

[66] Barron in Barron and Eckmann, p. 18, Karen Lang, “Expressionism and the Two Germanys,” in Barron and Eckmann, p. 90.

[67] Barron in Barron and Eckmann, p. 19.

[68] Richard Langston, The Art of Barbarism and Suffering,”in Barron and Eckmann, p. 241, 254.

[69] Idem, p. 242.

[70] Idem, p. 241, 242.

[71] Idem, p. 250.

[72] Huyssen in Barron and Eckmann, p. 235.

[73] Lang in Barron and Eckmann, p. 93.

[74] Barron in Barron and Eckmann, p.18; Lang in Barron and Eckmann, p. 93.

[75] Peters and Prügel in Barron and Eckmann, p. 82; Lang in Barron and Eckmann, p. 96.

[76] Peters and Prügel in Barron and Eckmann , p. 78.

[77] Idem, p. 80.

[78] Huyssen in Barron and Eckmann, p. 225.

[79] Peters and Prügel in Barron and Eckmann, p. 80; Matthew Bailey, “East and West: Markus Lüpertz and Anselm Kiefer,” in Barron and Eckmann, p. 332.

[80] Huyssen in Barron and Eckmann, p. 225.

[81] Eckhart Gillen, “Scenes from the Theater of the Cold War of the Arts,” in Barron and Eckmann, pp. 283.

[82] Huyssen in Barron and Eckmann, p. 237; Diedrich Diedrichsen, “The Leftists Artist: Visual Art and its Politics in Postwar germany,” in Barron and Eckmann, p. 143.

© Disturbis. Todos los derechos reservados. 2011